Period | Return |

|---|---|

| 2020 (starting 11 November 2020) | +3.42% |

| 2021 | +18.09% |

| 2022 – 1Q | -22.50% |

5 May 2022

Dear Co-Investor

The SaltLight SNN Worldwide Flexible fund returned -22.50%[1] for the 1st quarter of 2022. A volatile period that I’m sure has you questioning whether you want to be in equities, global investments and, perhaps, this steward of your capital.

For us, these turbulent periods are somewhat cathartic for our investment process. Investing mistakes are usually made in the ‘good times’ when the price one pays can diminish the returns on even the most wonderful businesses because future price expectations are based on a hopeful set of outcomes rather than probabilistic realism.

Conversely, when prices are falling rapidly, and market participants are attempting to curtail any sort of emotional pain attached to quotation losses (Kahneman’s Loss Aversion theory), our delight is that prices reflect irrational assessments of a distribution of outcomes.

The job of an opportunistic investor is to put a helmet on, take a deep breath and get on with capitalising on these rare moments that are offered once or twice a decade.

This letter will be somewhat shorter than our usual letters as we have our heads down in research looking at several businesses that were previously too expensive for our investment criteria.

We must re-iterate that over the long-term, despite what the overwhelming noisy elements in financial markets tell us, at the end of the day, prices follow the earnings power of a business – not interest rates, inflation, or global geopolitical events.

Our definition of ‘resilience’ that we look for in our portfolio companies comes from the anti-fragility of earnings power over time and not a business that has a low volatility share price. Volatility is the price of being in public markets.

We generally hesitate to over-cook our precious quarterly communications with you by discussing short-term events that are likely to be ‘old news’ in a few quarters. But we thought it would be helpful to contextualise three items that contributed to the volatility in our quarterly return: (1) The Strong Rand, (2) China, and (3) Developed Market Technology Exposures.

We also provide some detail about the resilience in our portfolio by talking about our investment in Brookfield Asset Management.

The Strong Rand

As c. 80% of our fund is non-ZAR denominated, Rand strength negatively impacts our return reported in Rands. During the first quarter, the USDZAR appreciated from R15.91 to R14.55 (approximately +8.5%). Whilst our portfolio companies are distributed across multiple geographies, a large proportion (including the Chinese ones) are denominated in USD. Over time, we believe that the odds favour the ZAR depreciating but we have zero confidence in making any short-term predictions and so we simply carry on with our business without spending too much time thinking about how to avoid such movements.

China

At the quarter-end, we have roughly 14% direct exposure to Chinese companies. Over the last year, China has been a persistent detractor of returns in the short term.

It feels like it has been a case of one thing after another: technology regulations, a real-estate downturn, geopolitical re-positioning and what we believe, is a futile zero-COVID strategy.

We went through this very similar ‘cloudy period’ in South Africa only a few years ago: negative sentiment, rock bottom valuations and seemingly unending negative events.

We learned during that period that when investor sentiment at a country level is very pessimistic, ‘resilient’ businesses are often lumped together with mediocre ones. Of course, they’re not immune to weak economic conditions but we’ve found that when the tide turns eventually, it is the ‘resilient’ companies that bounce back quickly.

We’ve written about this before, but an investor’s job is to make probabilistic bets on an unknown future. We’ve applied our learnings from that SA period to our China investments. We think that the distribution of outcomes relative to the valuations of some of the businesses that we own are extremely favourable.

US technology-related share prices have been extremely volatile. The NASDAQ was down ~10% for the quarter, and year-to-date, it is down ~-22% in US Dollars. Despite these drawdowns, the indices obscure the real declines in sub-$100bn market cap companies, that have seen drawdowns of 25%-70%.

Developed Market Technology Exposures

Several factors are intersecting to create uncertainty for market participants: (1) COVID beneficiaries are showing slower growth, (2) rising interest rates, (3) war and now (4) recession fears.

In our March update, we mentioned this quote by James Anderson, manager of the Scottish Mortgage Investors Trust “In the short term, almost anything can matter. In the long term, it’s the deep reasons of success and compounding, that should matter to us and where we can have a difference of view from others.”

Our investment process is concerned with how a business will look in 2028. Across our portfolio companies, our businesses are substantially larger since COVID-19, many are solidifying or extending their competitive position and are finding new ways to serve their customers better every day. We continue to believe that ‘winners’ will get stronger over the long term albeit at a slower growth rate than during COVID.

Resilience, Indispensability and Durability

During times like this, it is always helpful to remember what your portfolio is built with. One company that we’ve alluded to in the past is Brookfield Asset Management (BAM). We’ve been invested in BAM across our various funds since 2019 and could not describe a more ‘resilient, indispensable and durable’ portfolio company.

BAM is one of the largest alternative asset managers in the world, but it has some nuances that make it screen poorly (we’ll get into that). It started life as an industrial conglomerate called Brascan in Canada and so in line with general Canadian culture is understated and stays out of the limelight.

| Return CAGR Over Period | BAM Share Return | S&P 500 | Relative Difference |

| 1 Year | 48% | 29% | 19% |

| 5 Years | 24% | 18% | 6% |

| 10 Years | 20% | 16% | 4% |

| 20 Years | 20% | 10% | 10% |

| 30 Years | 17% | 11% | 6% |

Source: Company

Bruce Flatt has been the CEO for over two decades and is the type of manager that we seek to partner with: honest, trustworthy, and extremely capable. We highly recommend watching these two videos: a Google talk in 2018 and this David Rubenstein interview to get a sense of Flatt.

Importantly, BAM is not just about Flatt and his singular investing skills as many asset managers are. This is a widely scaled business. We’ve been impressed with the calibre of up-and-coming executives operating the individual businesses which give us confidence that the BAM culture will be retained for many decades to come.

BAM is unique in that it is an asset manager of third-party capital (called Limited Partners or LPs) but it also co-invests with its investors using its own capital. It certainly eats its own cooking (something that we can resonate with).

Therefore, the intrinsic value should be comprised of invested capital plus the discounted value of future fee income. On top of this, if they generate outsized returns, they earn performance fees over an agreed-upon hurdle rate (called “carried interest”).

BAM has an enviable track record, but a big part of their differentiation is that they run an internal operating business as well. Alongside investing staff, they have operators, engineers and domain experts that can optimise the operations of their investments. This allows them to buy cheap ‘fixer uppers’, send in their operators and re-sell them at a premium valuation. This is their secret sauce.

What Does BAM Invest In?

BAM started off investing in ‘real assets’ – real estate, power stations and toll roads. Over time, it has expanded into private equity investments related to real assets, data centre infrastructure and recently ‘green’ assets.

Unlike public equities, these assets can be highly illiquid and so BAM raises funds from LPs where capital is locked up for at least a decade. In recent times, they’ve been able to raise perpetual capital that never needs to be redeemed to investors. For each fund, BAM will earn management fees for the fund’s duration and so their earnings are highly predictable for many years to come.

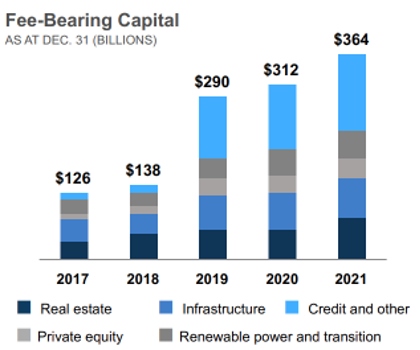

As of December 2021, BAM had $688 bn[2] (that’s a billion, not a million) of assets under management, of which, US$364bn is fee-bearing capital. Over the last five years, BAM has been able to grow fee-bearing capital from US$126bn to US$364bn. Part of this growth came acquisitively when BAM bought Howard Marks’ firm Oaktree for their credit investing capabilities.

As these large asset managers scale, they aim to be a one-stop-shop for their clients. Given the long duration of BAM’s assets, BAM is a perfect product supplier to endowments, family offices and insurers that have long-duration capital. BAM has started to expand its investment expertise not just in the equity level of the capital structure but also in debt (a principal reason for the Oaktree acquisition).

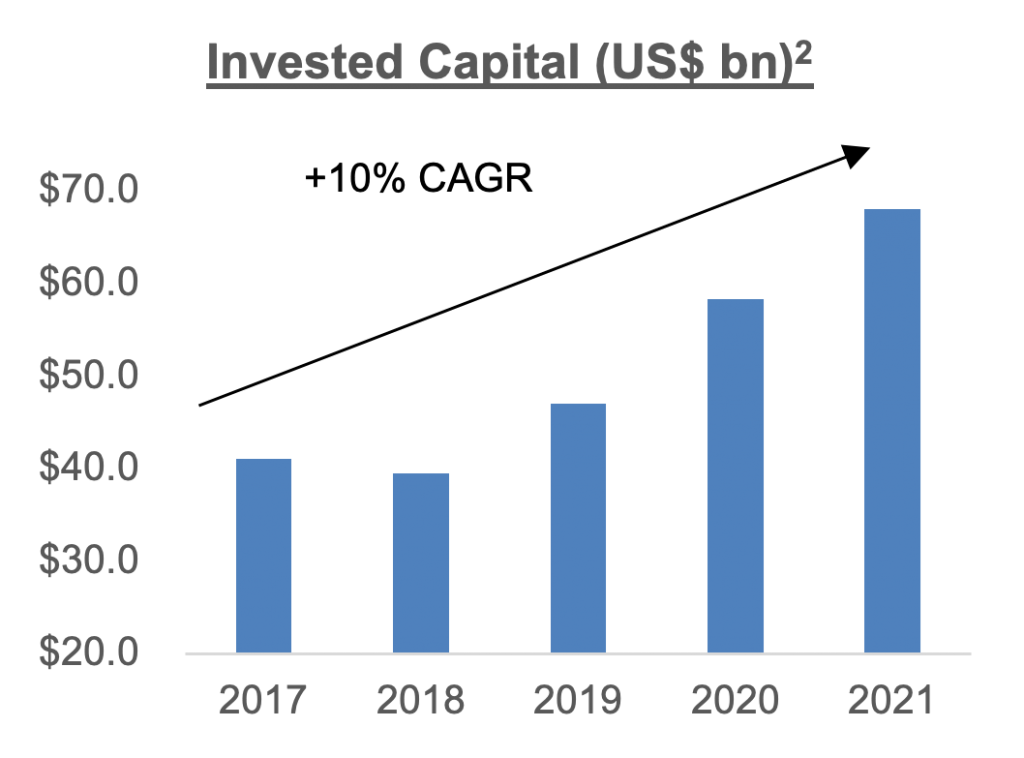

The ‘on-balance-sheet’ capital that we as shareholders own is valued at around US$68bn[3]. This will fluctuate with market conditions, interest rates etc but we should mention that the current market cap is around $78bn (which should reflect the on-balance sheet capital plus fee-related businesses). We think the business is highly undervalued.

Size is the Enemy of Returns?

In investing, the larger a fund grows, the consequence is that outsized returns start to diminish because large funds can’t take advantage of every opportunity. However, in the case of real assets, size is an advantage. If, say, a government is looking to privatise a hydroelectric station to pay down sovereign debt, the investment size would be too big for most funds and so multiple parties and bank syndicates would have to make a bid. Whereas BAM can write a large cheque and operate the asset too. It is a meaningful differentiator to an asset-seller like a government that will face public scrutiny if the buyer performs poorly with a public asset.

Given that they invest their own capital and that they manage the 3rd party funds that also own their portfolio assets, the accounting rules say that BAM must consolidate all their businesses onto the balance sheet – including the debt. Economically BAM partakes in say 10-15% of the underlying assets, but from an accounting perspective, it looks like they have 100% of the debt. BAM’s track record means that they have negotiated with the banks that the portfolio company debt is non-recourse to the holding company and so if one portfolio investment goes bankrupt, the impact is compartmentalised. This critical feature is very important for the resilience of the business as a whole.

Few competitors can match BAM’s size and so there is a two-sided moat that continues to grow. BAM can get access to assets that most asset managers can’t reach – particularly real assets. Secondly, on the capital pool side, it is a highly attractive proposition to a capital allocator that they can allocate $10bn cheques to one firm.

For 99% of asset managers, a $10 bn fund is a large end-state goal. BAM is raising $100bn a year and can deploy it at scale.

Future Growth

At almost $360 bn of fee-bearing assets, one would be concerned that the growth of the business is limited. However, management expects to grow fee-bearing assets under management to $830 bn over the next five years.

I’d like to talk through two of their new innovative businesses that illustrate the entrepreneurial culture and optionality in the business:

1) Insurance

It is a well-written topic in finance circles (and a quiet whisper amongst politicians) that ageing populations and their pension liabilities will require very high returns to be funded (the average US nominal return assumption is 7.19%[4] when long term US treasuries are earning ~3%).

BAM has started a new business where they are buying up reinsurance businesses that offer annuity reinsurance. Given that BAM has long-duration assets that earn better than 7%, they will take on the liability risk from a pension fund through a reinsurance risk transfer product.

Their timing has been impeccable. Declining interest rates have been an incredible investment for asset holders since the 1980s. One person’s asset is another’s liability and so declining interest rates mean that long-duration liabilities (such as a pension obligation) have also grown larger.

BAM is essentially taking on these liabilities away from a pension fund as interest rates have bottomed. Over the next few decades, we don’t know if we will see sub-zero interest rates again, but from a BAM perspective, they’ve bought these liabilities at near the worst that they could ever be. If BAM can generate a better spread from their assets, this new business should do very well.

Management thinks it can add $200bn-$300bn of new assets (currently $40bn at year-end) through this business.

2) ‘Green’ Transition Funds

The Transition Funds aim to capitalise on the abundance of ‘green’ mandates. BAM is already the largest investor in renewables (generating 59,846 GWh across hydroelectric, wind and solar assets) but they see a multi-decade investment cycle to meet the Paris Agreement Net-Zero 2050 Goals).

Their new Transition Funds are run by Mark Carney (former Bank of England Governor) that will invest in two pillars:

- Expanding investments in owning and operating renewables (50%)

- Buying stakes in non-green businesses (steel, cement, and chemicals) that are priced for ‘ESG[5] death’ and to assist them with capital to bring down their carbon footprint (and hopefully re-rate their investment value).

Potential Corporate Action

As we’ve indicated, we think BAM is highly undervalued for the predictability of fee income and future investment opportunity set. Currently, the market attaches zero value to the unrealised carried interest earned (~ $4.7bn at 4Q21)[6]. Comparably large asset managers only have fee-earning businesses and do not reinvest their own capital in the underlying funds. BAM’s Management believes that the market is undervaluing the firm because they have both.

During the quarter, management announced that they’re considering splitting their ‘asset heavy’ investments and the ‘asset light’ asset management business. Nothing has been crystalised, but this could be an additional value unlock.

*****

Whilst several elements caused some volatility in our fund, we sleep well at night when we consider our investment portfolio. Share price movements do not reflect the strength of our portfolio.

As always, we remind you that like BAM, almost all of our liquid personal wealth is invested in the same fund as yours. We share in the inevitable ups and downs with you.

We recognise that strong drawdowns like these are unpleasant and we have the benefit of deeply understanding our investments so that we can sleep easy at night and not worry about volatility. We understand that you as a client see an investment fund as a black box beyond what is communicated in ten or so pages once a quarter.

Incredibly we have seen no significant redemptions which is an absolute testament to the long-term mindedness of our client base. We salute you and thank you for your continued partnership.

We would love our investors to have a great experience partnering with us and so any investor who wishes to talk through any aspect further, please feel free to give us a call.

Warmly,

David Eborall

Portfolio Manager

[1] Return for the A1 class of the SaltLight SNN Worldwide Flexible Fund. Individual class returns may differ.

[2] Source: Company

[3] Management valuation at 31 December 2021. If the debt and preferred capital of ~$15bn is excluded the equity value is roughly $53bn

[4] Source: NASRA Public Pension Plan Investment Return Assumptions

[5] Environment, Social and Governance

[6] Source: Company. Unrealised Carried Interest after direct costs. Unrealised carried interest is carried interest earned on existing funds based on current valuations. A manager only earns this carry when the asset is sold, and the carry is then ‘crystalised’

Disclaimer

Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. The value of participatory interest (units) or the investment may go down as well as up. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance. Collective investment schemes are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. A Schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions, as well as a detailed description of how performance fees are calculated and applied, is available on request from Sanne Management Company (RF) (Pty) Ltd (“Manager”). The Manager does not provide any guarantee in respect to the capital or the return of the portfolio. The Manager may close the portfolio to new investors to manage it efficiently according to its mandate. The Manager ensures fair treatment of investors by not offering preferential fees or liquidity terms to any investor within the same strategy. The Manager is registered and approved by the Financial Sector Conduct Authority under CISCA. The Manager retains full legal responsibility for the portfolio. FirstRand Bank Limited is the appointed trustee. SaltLight Capital Management (Pty) Ltd, FSP No. 48286, is authorised under the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act 37 of 2002 to render investment management services.